This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

BEFORE Hobson (1902) and Lenin (1917) elaborated theories of imperialism, there was an American Anti-Imperialist League (1898).

The league’s members constituted a diverse group, ranging from left to right, radical to conservative, social worker to politician, writer to lawyer, trade union leader to monopoly capitalist.

Notables included Jane Addams, Grover Cleveland, Andrew Carnegie, John Dewey, Samuel Gompers, Henry and William James, Edgar Lee Masters and Mark Twain.

While they may have had differing views of the actualities of imperialism or colonialism, the Anti-Imperialists shared a sense that a tide of imperial or colonial predation was cresting at the end of the 19th century.

Moreover, they feared that the US was energetically joining the mainly European powers in carving up the world.

This opposition was built upon two principles that were thought by many to be foundational US ideals: the idea of consent by the governed and non-intervention (like so many contradictory ideals in US history, the 19th-century US anti-imperialists seemed little bothered by intervention and lack of consent with the frontier expanding across the American continent at the expense of others).

To those constituting the American Anti-Imperialist League (AAIL), imposing the will of imperial masters upon other peoples violated the most basic axioms of democracy.

To the anti-imperialists of the AAIL, it mattered not whether those to be governed by others governed themselves well or not.

The partisans of the AAIL were unmoved by the pro-imperialist arguments that people’s souls needed Christian salvation, that subjected peoples would be better off surrendering their sovereignty, or that those to be ruled were savages and incapable of ruling themselves.

In US history, the mass predisposition towards non-intervention was only interrupted when ruling elites were able, through fear or fable, to animate involvement in outside adventures; non-engagement in foreign affairs was deeply embedded in popular thinking as well as in the early expressed values of the colonial regime.

Mark Twain, one of the US’s greatest writers, perhaps best expressed the anti-imperialist sentiment of the time in 1905 with his satirical King Leopold’s Soliloquy (During the cold war, this powerful anti-imperialist critique was only available in book form from a GDR publishing house).

Twain scolded Leopold, the King of Belgium, and his brutal colonial reign over the Congo.

Through the fiction of an explanation by the King, Twain mocks the King’s justification for his mistreatment of his subjects, citing his missionaries bringing civilisation to the natives and his thwarting of the evil slave trade.

Thus, Twain, like most of the 19th-century anti-imperialists, thought that there was no good reason for great powers, or any powers for that matter, to intervene in the affairs of another land, regardless of the good they might bring or the evil they might thwart. Put simply, intervention violated the consent of the people.

In the 20th century, this understanding of anti-imperialism was sharpened by Lenin’s right of a clearly defined nation to self-determination.

This idea of self-determination served as the grounds for national liberation and the almost total elimination of colonialism, a process largely, but not completely finished in the decades after World War II.

As in Leopold’s time, the imperialists maintained that the native peoples were not ready for self-rule.

While colonialism receded, imperialism remained, with US imperialism and its global domination of the capitalist world taking centre stage.

The foe for the US and its European allies in this era was world communism. Communism, whether viewed favourably or not, was undeniably the bulwark against imperialist domination.

Cold war imperialism justified intervention in the affairs of other nations as part of an unrelenting war against communism.

Intervention was a prophylactic or remedy for an evil portrayed as godless, materialistic, murderous, anti-democratic, ruthless and predatory.

Like Leopold and his counterparts, 20th-century capitalism and its apologists defended economic aggression as a civilising mission, as a way to bring a superior way of life to those captured or courted by an evil ideology.

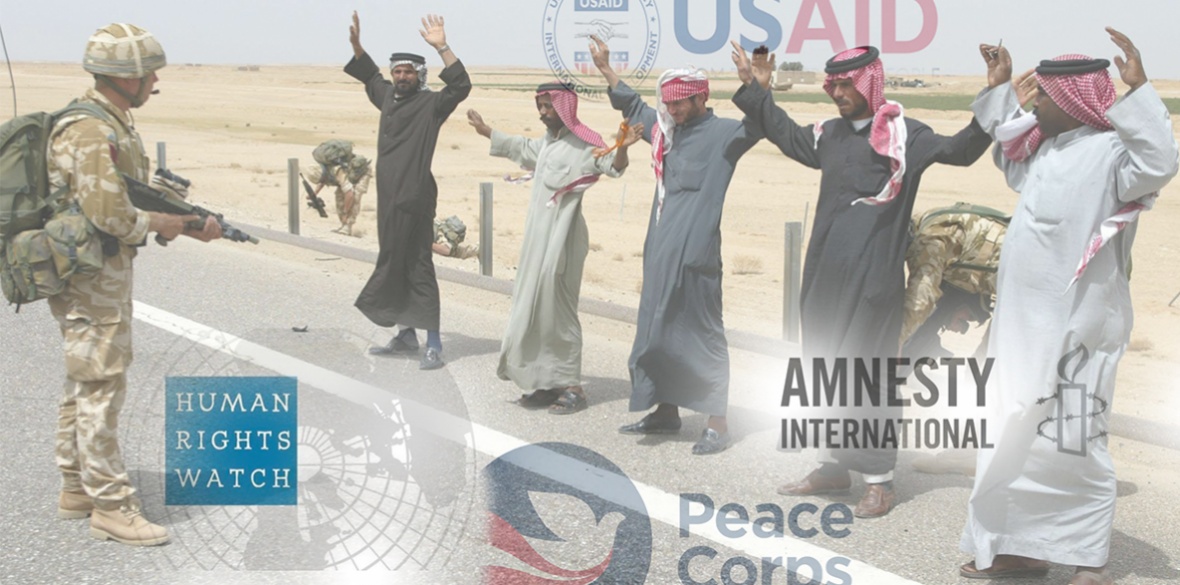

USAid, the CIA, money-soaked foundations, cultural warriors, the Peace Corps, etc, replaced the 19th-century missionaries.

When these modern missionaries became ineffective, the US military stepped in.

In our time, many self-styled anti-imperialists have lost the meaning of anti-imperialism that was so firmly grasped by our 19th-century forbears.

Under the sway of the cold war corruption and weaponisation of human rights advocacy, liberals and a segment of the left now qualify their condemnation of US and EU domination of less powerful countries with real or imagined concerns with human rights violations or the perceived breaching of democratic standards.

They have become the modern missionaries, purveyors of supposedly superior Western values to the ignorant and backward of the world.

Like the missionaries of old, they spend little time in self-examination — they simply take for granted that their way of life is superior in all ways.

With that presumption, it is a small step to finding merit in intervention, in bringing enlightenment, even liberation. And, of course, the messenger or the deliverer of enlightenment may well be US bombs, special forces or mercenaries.

Whether it is Haiti, Iran, Guatemala, Cuba, Nicaragua, Grenada, Yugoslavia, Iraq, Venezuela, Libya, Syria, or many that I may have left out, all interventions were justified as humanitarian missions delivering a better way of life. Those who succumbed to this bogus liberation are all now broken or failed states.

Where human rights doctrines served a liberating purpose, unleashing human potential and providing protection against feudal caprice and privilege during the rise of capitalism, they now are more often instruments of manipulation and oppression in the era of moribund, decadent capitalism.

Western NGOs underscore this point. In the cold war heyday of Amnesty International, one could not help but note that the organisation’s focus was largely on the socialist countries and their friends.

This was explained by the peculiar rule that it was inappropriate for Amnesty chapters to focus on their home country.

So, of course, since the membership was largely in advanced capitalist states, the spotlight was upon non-capitalist and anti-capitalist states. A mere formality that put the organisation, more often than not, in lockstep with the US State Department and Nato.

Another prominent NGO — Human Rights Watch — came into being as an anti-Soviet watchdog. Its funding — largely from the US and Europe — cannot but taint the targeting of its attention.

It is equally clear that the “human rights” NGOs show much less zeal in exposing the “friends” of the US, EU and Nato who had appalling human rights records.

They were late or tepid in deploring the ugly apartheid regime in South Africa, the brutal treatment of Palestinians and the Saudi aggression against Yemen.

The gaggle of NGO directors that police the human rights terrain form a comfortable team with academics, think tanks and the professional crusaders of Western political officialdom.

They attend the same seminars, consult one another and often exchange jobs, guaranteeing a high degree of conformity and insularity and generating a human rights industry.

There is a comfortable circularity to Western human rights doctrine. Of the expansive range of human rights — positive, negative, personal, social, individual, collective, cultural, commercial, etc — it is exactly those rights that are the most cherished by the self-satisfied capitalist burgher that NGOs rush to protect! And they are protected with missionary zeal.

It is this industrial-strength human rights doctrine that mixed with US foreign policy goals to create the twisted notion of “humanitarian interventionism,” a concept most successfully peddled by and identified with former political operative, diplomat and now head of the CIA-front USAid, Samantha Power.

Thus, the twisted trajectory of human rights advocacy has led us to an equally twisted concept of benign intervention, an idea that would have outraged earlier advocates of anti-imperialism like Mark Twain, Samuel Gompers and even Andrew Carnegie.

As if critics of US foreign policy did not have a great enough burden, large sections of the US left — especially those addicted to the New York Times and National Public Radio — have gone over to the other side, drinking the seductive elixir of humanitarian interventionism.

The NYT/NPR “progressives” and their European counterparts qualify their anti-imperialism by insisting that those countries under the heel of imperialism must pass a purity test: they must be committed to “democratic” and “human rights” values that are consistent with those of their oppressors and privileged Western “progressives,” otherwise, they will not win the support of their “friends” in the Western capitalist countries.

We have seen this time and time again in the refusal to or hesitation in denouncing imperial aggression in Yugoslavia, Syria, Iran, Venezuela, Libya and even Cuba.

This arrogant, selective “anti-imperialism” would nauseate the 19th-century anti-imperialists of the AAIL.

The gutted anti-imperialism of humanitarian interventionism recently found its theoretician in Professor Gilbert Achcar. Achcar wrote a piece happily embraced by the old cold war campaigner New Politics magazine and the increasingly irrelevant weekly, the Nation.

A consistent anti-imperialist comrade, Roger D Harris, thoroughly dismantled Achcar’s apologetics for US, EU and Nato imperialism in his response.

Harris correctly argues that Achcar and the other “sophisticated” anti-imperialists “(1) serve to legitimise reaction and (2) obscure the singular role of US imperialism, while (3) attacking progressive voices. Such anti-anti-imperialism provides left cover for the foreign policy of the US as well as the UK, where Achcar is based.”

In plain words, the bogus anti-imperialism of humanitarian interventionism turns a blind eye to the global bully because the victim is not always “worthy” of defence. This response is especially indefensible when the global bully attacks in our name.

Regardless of how the New York Times, NPR or the other media pals of the bully portray the victim, a bully is still a bully. Our 19th-century forbears understood this simple truth.