This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

WHEN Jackie Robinson joined the Brooklyn Dodgers of Major League Baseball, the team’s president and general manager, Branch Rickey, was concerned as to how his new signing would respond to racist abuse.

Robinson had a history of fighting back.

While in the military he was recommended to be court-martialled for refusing to move to the back of a bus by a driver who enforced racial segregation even on an unsegregated army bus, and for subsequent confrontations with military police related to that incident.

This was part of the reason Robinson was signed by Rickey, who recognised the player needed to be strong in the face of segregation and abuse.

But Rickey also wanted Robinson to rein in his instinct to fight back.

An article for ESPN by Larry Schwartz recounts a condensed version of the conversation between Rickey and Robinson.

Rickey: “I know you’re a good ballplayer. What I don’t know is whether you have the guts.”

Robinson: “Mr Rickey, are you looking for a negro who is afraid to fight back?”

Rickey: “I’m looking for a ballplayer with guts enough not to fight back.”

This was 1945. Robinson was the first black player to play in Major League Baseball, breaking the sport’s colour line that had previously seen black players excluded from the major leagues and limited to a separate competition called the Negro Leagues.

As a pioneer and a trailblazer, he was expected by Rickey to clear the way, not to add further complications.

It was an unreasonable ask, but at a time when racism and segregation were still rife, and in many places the accepted norm, Rickey thought it necessary.

In 2024 it should be ludicrous to suggest that a black player keep quiet in the face of racist abuse. That they should keep their head down and not fight back. That they should rein in their confidence and expressive ability to avoid being a target for racism.

But it appears this is what many think the 23-year-old Real Madrid and Brazil footballer Vinicius Junior should be doing.

Vinicius is currently one of the best players in the world. A star player in the post-Lionel Messi, post-Cristiano Ronaldo era.

He’s a skilful showman in the way other great Brazilian wingers before him have been. A two-time league champion (likely soon to be three-time) and a Champions League winner. He also finished sixth in voting for the 2023 Ballon d’Or.

He has also become a regular target for racism in Spain, during games and in their aftermath as figures within the game try to excuse it.

After being racially abused at a game in Valencia in May 2023, Vinicius responded: “It was not the first time, nor the second, nor the third. Racism is normal in La Liga.

“The league considers it normal, the federation considers it normal and the opponents encourage it.

“The league that once belonged to Ronaldinho, Ronaldo, Cristiano and Messi today belongs to the racists.”

Racism today is normalised in different ways than it was when Robinson joined the Dodgers in the 1940s, but it is still normalised nevertheless.

Spanish sports journalist Kike Marin tweeted this week, “It is not racism, it is Vinicius.”

Marin’s tweet included three videos of Vinicius fighting back, with the suggestion being the player brings racism upon himself through his actions and words.

It’s a common excuse (the tweet has almost 2,000 likes) and the excuse is itself an extension of the racism Vinicius receives at his workplace.

They are effectively saying racism is acceptable because the player fights back.

It is almost an admission that the world is just as racist now as it was 80 years ago — that any prominent black professional athlete should keep a low profile and not fight back against racism lest they aggravate the situation.

La Liga president Javier Tebas said last week in an interview with Politico that racist incidents “don’t happen all the time or a lot, and they are mainly focused on Vinicius.

“Maybe that’s because Vinicius is leading a case against racism so that’s why we have these isolated events that attack him,” Tebas added.

“So what La Liga is doing is to protect Vinicius as much as we possibly can.”

But it doesn’t appear that La Liga is doing much to help him at all.

This month Real Madrid filed a complaint to the Spanish authorities over alleged racist chanting towards Vinicius from Atletico Madrid and Barcelona fans at these clubs’ respective Champions League last 16 games versus Inter Milan and Napoli. Games not even involving Real Madrid or Vinicius.

“I hope you’ve already thought about their Champions League punishment, Uefa,” Vinicius responded last week. “It’s a sad reality this happens even at matches I’m not at.”

Vinicius does have some support from within the game, and from within his club.

“The Spanish league has a problem, and it’s not Vinicius,” Real Madrid manager Carlo Ancelotti said last year. “Vinicius is the victim. The problem is very grave.”

Brazil’s President Lula said: “It is not fair that a poor boy who is winning in his life, becoming one of the best in the world, certainly the best at Real Madrid, is insulted in every stadium he goes to.

“We can’t allow fascism and racism to dominate inside a football stadium.”

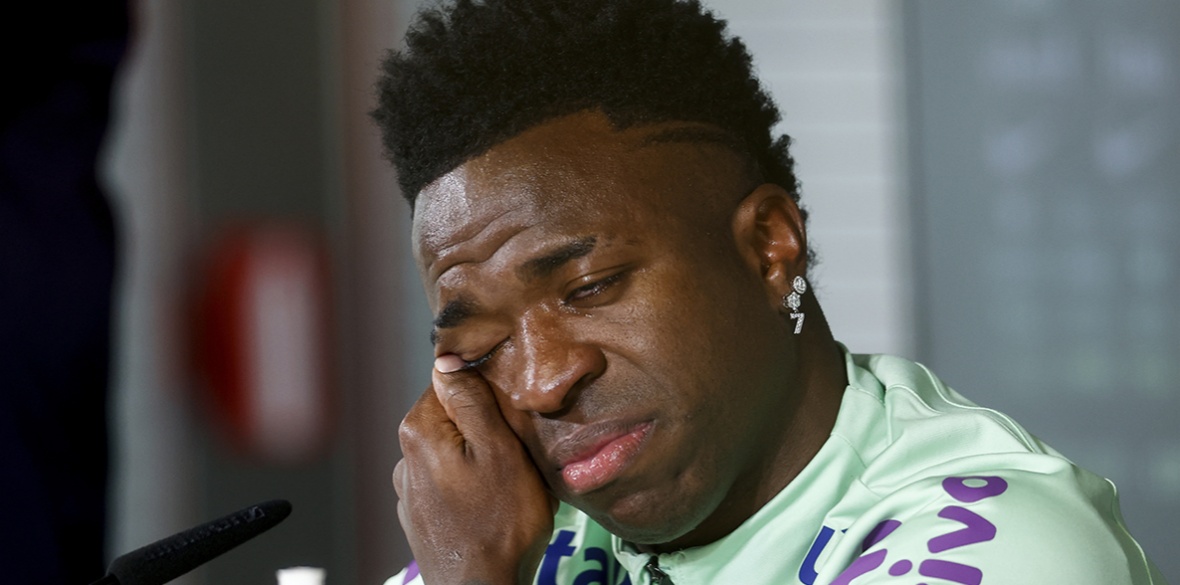

Vinicius broke down in tears at a press conference last week ahead of Brazil’s friendly against Spain.

The game was set up as an event to highlight racism in football and work to combat it, but the Spanish federation’s involvement and promotion of this aspect of the fixture was tepid at best.

It’s something Vinicius is sadly used to.

“It's exhausting because you feel quite alone in this battle,” he said in the pre-match press conference, translated via Agencia Brasil.

“Despite my numerous complaints, no-one is held accountable, no club faces punishments.

“Each day when I return home, I feel more disheartened, but I've been chosen to champion such an important cause.

“I study more [about racism] daily, learning so that in the very near future, my five-year-old brother won't have to endure what I'm going through.

“I’m 23 and I’m still learning. Why can’t the Spanish reporters, who are older than me, study and see what's really going on?

“I’m getting sadder and sadder, I feel less and less like playing, but I’m going to keep fighting.

“I’m going to stay here fighting, playing for the best club in the world, winning titles and scoring goals, and they’ll have to see my face even more.”

Vinicius wants measures put in place so that racists are the ones who are scared and afraid to air their views at football stadiums, but instead, it is currently Vinicius who goes into every game apprehensive.

It is 79 years since the colour line was broken in baseball and Jackie Robinson was encouraged to stifle his instincts to fight back against racism so that other black players could follow in his path.

Vinicius is not breaking a colour line and he is not the first professional black footballer, but it feels like he is facing many of the same challenges Robinson faced.

It shouldn’t be the case that in 2024 a high-profile black athlete is still expected to grimace and bear it.