This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

THAT tough times produce tough people is an urban myth that has long peppered working-class life — as if having to be tough to survive is something to be proud of rather than something to lament.

And what is toughness anyway? Is it a form of courage, a willingness to harness violence in pursuit of self-interest — material and status — or is it the ability to suffer and endure privation without being broken by it?

Those very questions have tantalised and occupied the minds of philosophers stretching all the way back to Aristotle, who once opined: I count him braver who overcomes his desires than him who conquers his enemies; for the hardest victory is over self.”

In no other field is “victory over self” more important than in the sport of boxing. Processing the natural human fear of physical violence and pain, and ultimately overcoming it, is the non-negotiable criterion for not only success but survival in a boxing ring.

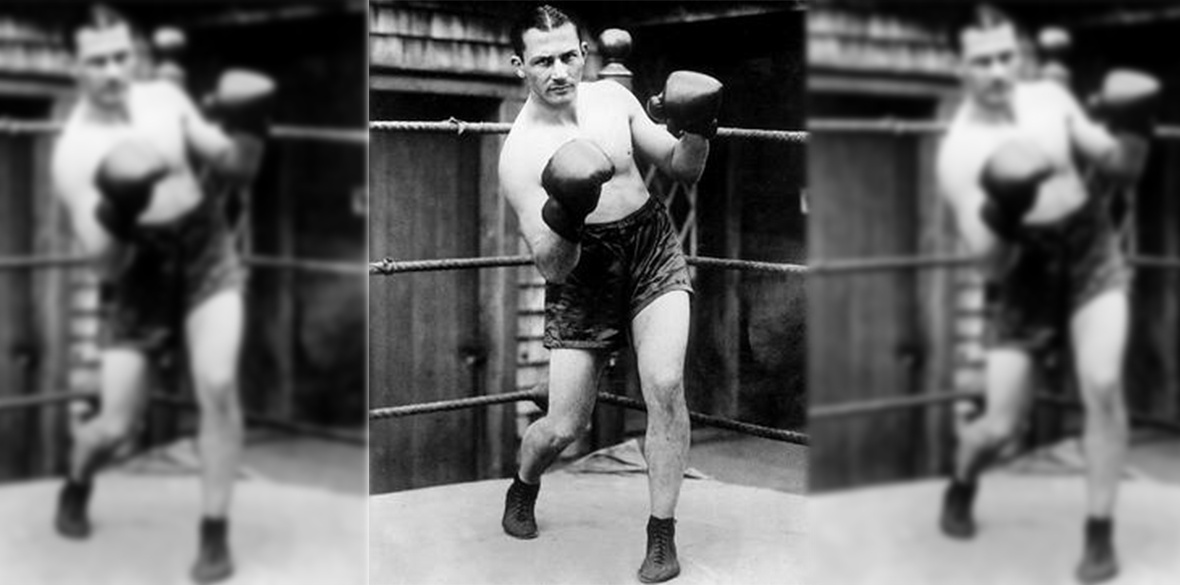

One fighter who more than overcame this fear, and who also helped his people overcome theirs, was the famed and legendary lightweight world champion, Benny Leonard.

Born Benjamin Leiner in the Lower East Side of Manhattan in 1896 to Russian orthodox Jewish immigrants, Leonard was destined to carry on his shoulders the weight of a Jewish community suffering the ravages of anti-semitism on one of the lower rungs of the ladder of American immigrant status.

The spike in anti-semitism across the United States in the late 19th century was in large part a consequence of the influx of Jewish immigrants to the country from Europe, where across Eastern Europe in particular anti-Jewish pogroms were then rife.

Poverty was endemic in the country’s massive conurbations - and nowhere more so than New York - as working class people competed for evermore scarce employment opportunities. Such conditions are ripe with the opportunity for racial and religious bigotry to spread, and with Jewish immigration the predominant kind in this period, anti-semitism became more overt than it ever had or has been in the land of the free.

Out of this toxicity emerged Benny Leonard, who like many ring legends of this era began his fighting career in the streets. There he and others from the same Jewish ghetto on Manhattan’s Lower East Side fought the children of other immigrant groups, mostly Irish and Italian, for bragging rights and to protect their turf. Over the course of these regular street battles, Leonard established a reputation for being good with his fists. With seven siblings to be fed at home and a father whose pay from hard physical labour was paltry, Leonard seized the opportunity offered to him by his uncles to develop his talent for fighting at a local boxing club when he was just 11 years old.

With empty dinner plates on his mind, Leonard forswore the conventional path of learning his trade as an amateur and began fighting as a pro from the age 15 in 1911. He anglicised his last name at the same time, so as to avoid his parents finding out by reading about his ring exploits in the pages of the then popular Jewish Daily Forward. However he couldn’t avoid them finding out for long, and returning home after participating in a bout one evening, he later recounted that “My mother looked at my black eye and wept. My father, who had to work all week for 20 bucks, said, ‘Alright Benny, keep on fighting. It’s worth getting a black eye for 20 dollars; I am getting verschwartzt (blackened) for 20 a week’.”

Leonard rose through the ranks to become world lightweight champion in 1917, the same year that the US entered the first world war and the Russian Revolution shook the world. By now he had become the symbol of a new and rising muscular Judaism — representing Jews who weren’t going to take it anymore and would fight back — and in consequence he wasn’t just lauded he was revered by the Jewish community in New York and further afield.

As Jewish boxing scribe and movie writer Budd Schulberg remembered: “To see him [Benny Leonard] climb in the ring sporting the six-pointed Jewish star on his fighting trunks was to anticipate sweet revenge for all the bloody noses, split lips, and mocking laughter at pale little Jewish boys who had run the neighbourhood gauntlet.” In this sense, a Jewish champion of the ring like Leonard provided a strong counterpoint to popular anti-semitic tropes at the time.

The great trainer of a prime Roberto Duran, Ray Arcel, said of Leonard: “Boxing is brains over brawn. I don’t care how much ability you got, if you can’t think you’re just another bum in the park. People ask me who’s the greatest boxer I ever saw pound-for-pound. I hesitate to say, either Benny Leonard or Ray Robinson. But Leonard’s mental energy surpassed anyone else’s.”

Arcel's analysis of Leonard’s craft was spot on. A student of the game, Leonard approached boxing as if it was a game of human chess. He would spend hours at the gym studying other fighters to learn from their strengths and weaknesses, honing his own style into that of a defensive and counterpunching technician along the same lines as Floyd Mayweather Jr in his day.

At the time, the lightweight division was stacked with talent, making Leonard’s achievement in retaining the title for seven years all the more remarkable. Lightweights of the calibre of Johnny Dundee, Richie Mitchell, Charley White, Rocky Kansas, Johnny Kilbane, and Lew Tendler, Leonard fought and overcame.

Soon his fame transcended boxing to the point where Benny Leonard became a US cultural icon to the point where his fights became stadium events attended by crowds of 50,000 and more.

When he retired in 1925 he had amassed millions in the bank and looked set for a comfortable post-ring future. This changed abruptly with the 1929 stock market crash, which obliterated his savings and prompted his return to boxing. But as with most every champion who returns to the dance after retirement, Leonard was not the same animal and stuttered his way through to 1932, when he finally hung up the gloves for good.

Perhaps fittingly, given the extent to which boxing made and defined him, he died in the ring from a heart attack in 1947 while refereeing a bout in his beloved New York.

His legend still lives on to this day.