This is the last article you can read this month

You can read more article this month

You can read more articles this month

Sorry your limit is up for this month

Reset on:

Please help support the Morning Star by subscribing here

READERS will be aware of my deep frustration and anger at how the Arts Council of England – and many corners of the cultural sector – have failed the arts in the name of “anti-elitism.”

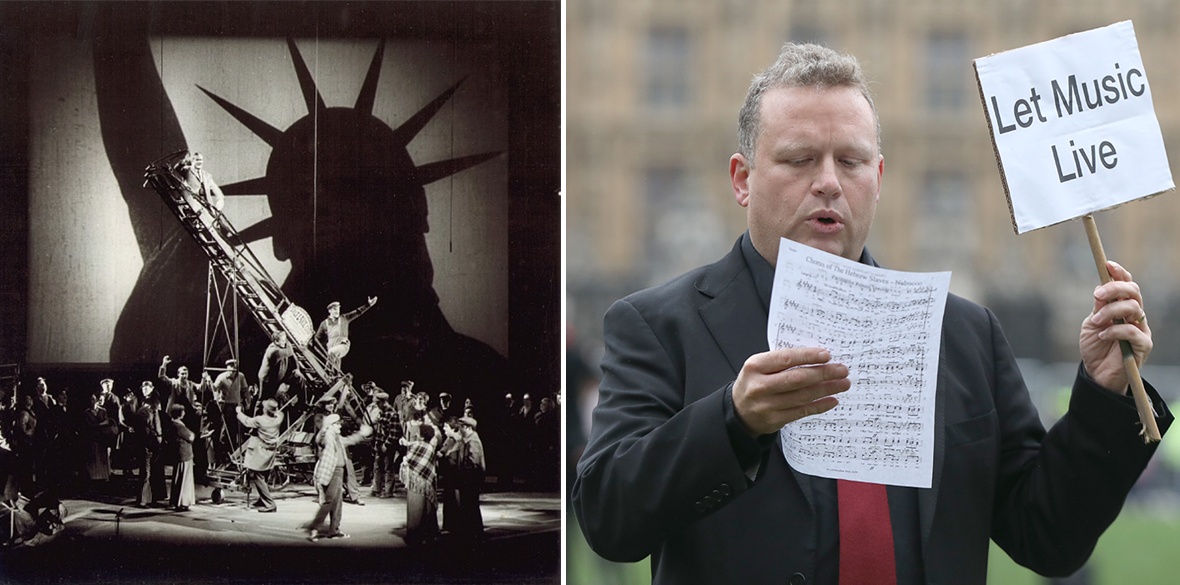

The new Let’s Create strategy from the Arts Council shows they are continuing to indulge in this closed-minded vision. Catherine Bennett from the Observer wrote a good breakdown of the immediate issues and lack of vision on display, and I’d recommend readers look at it, even if it means having to stomach the Guardian. In my opinion, we need to go further: to think as a class as we consider why we must fight for opera.

All art forms suffer elitism. Classical music, and opera specifically, have similar issues that we also see in poetry, the theatre, or art galleries. But we must never fall into the trap of considering that an art form itself is inherently elitist.

Opera, like all art forms, has evolved over a long period of time, and with this evolution has had incredible opportunities to explore radical ideas. Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, 1786, is an opera of class contention, where the canny Figaro uses wit and skill to defeat the lord and marry his true love; Beethoven’s Fidelio, 1805, tells the tale of Leonore who disguises himself as a prison guard to save Florestan from a political prison; Ethel Smyth’s The Boatswain’s Mate, 1914, is a wonderful demonstration of women’s tenacity and strength, despite what societal norms would suggest; and Luigi Nono’s Intolleranza, 1960, is a harrowing depiction of how brutal humanity can become, and how we can drift into such horrors.

In Britain today, there are many composers writing wonderful operas: Stuart MacRae, Lewis Coenen-Rowe, Bushra El-Turk, and Blasio Kavuma, to name a few. The reality, however, is that living composers are not given the chance to explore the grandeur of the form, working-class people are overlooked, the art form does not reflect our current circumstances, and there is a wealth of historic or recent work which is not explored due to fears that audiences are closed-minded.

Lenin pointed out the foolishness of not fighting on every political platform available. If we, as the left, feel the art form is not reflective of our class, then what are we doing to change that? We can complain about the current “elitism” that exists, but simply abandoning an art form means we lose the potential for radicalism to the wealthy, and we lose an art form that can bring so much joy simply from witnessing it.

Ultimately, we are not in a position to describe what a “true” working-class opera would look like. Rather, we have to be conscious of our long-term dreams and the steps we take today to get there. However, I want to draw attention to two composers in particular who demonstrate what can be done.

Sir Harrison Birtwistle, was born in Accrington, and is arguably one of the most significant British opera composers of the past century. He came from a working-class background. He didn’t get to his position through tokenism, but via talent. However, had he not had access to the art form his incredible voice would have been lost. His operas are not imbued with socialist rhetoric, but that doesn’t matter — because he is a clear demonstration of the talent that is being lost as we speak due to lack of access to the art form.

Alongside this, the operas of Alan Bush (The Press Gang, 1946; Wat Tyler, 1953; Men of Blackmoor, 1956; The Sugar Reapers, 1966 and Joe Hill, 1970), and Hanns Eisler’s opera/music theatre piece Die Massnahme, 1930, demonstrate that opera has the space to create political works. Meaning: if we campaign right and build in the right way, we can lay the foundations for a new composer to be the perfect marriage of these two elements. If we abandon opera, this will never happen within the “free market.”

As Sir Adrian Boult pointed out in the 1930s, the relationship between the state and the arts is complex but the situation we have now is a make-or-break moment. If we fall for the nonsense being fed to us by the Arts Council and their kin, the art form will be lost to the wealthy. If we want the art form to reflect us, and be available to us, the battle should focus on how we demand the brightest and best examples of the art form.

And ultimately, we should recognise that anyone who suggests that opera is not for the working class wants to con you into believing that eating crumbs is the progressive choice.